My Story

I’ve spent my life studying, understanding, and helping children and families—from my early years in New York, to training as a psychologist, to decades of research and forensic work. This is the story of what shaped my career, my values, and my commitment to children’s well-being.

Early Life

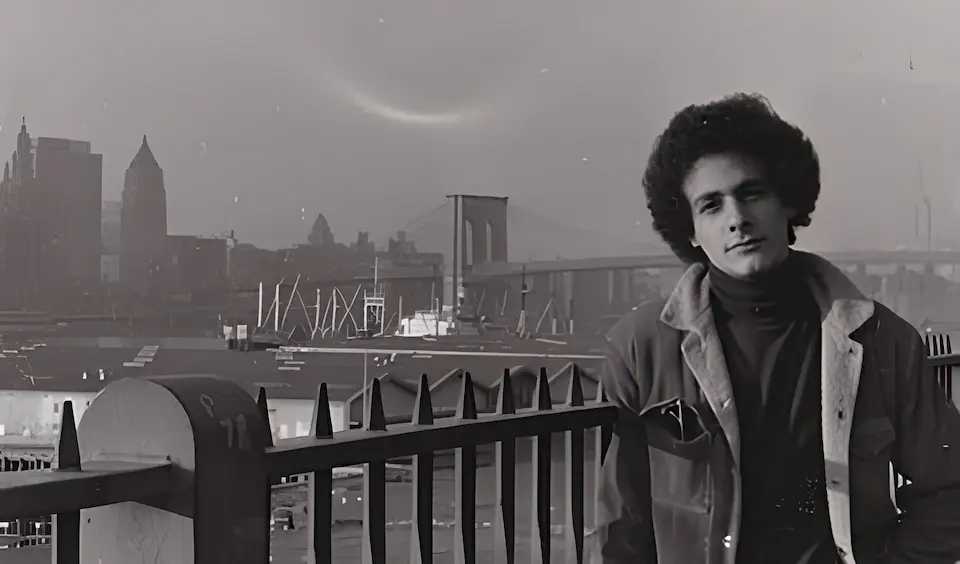

I was born in Manhattan in 1949, the second son of parents who remained married for 37 years until my father’s death.

Aside from my first two years in Manhattan, a short period in Caracas, Venezuela, and second and third grades in Jacksonville, Florida, I grew up in Brooklyn, New York.

I attended public school and graduated from Midwood High School when I was 16.

Cornell and the First Lessons in Conflict

I studied Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University during a turbulent period marked by escalating protests against the Vietnam War. In 1969, an armed takeover of the student union building interrupted classes and produced a Pulitzer Prize–winning photograph.

It was my first direct exposure to how unresolved conflict can erupt into crisis—an early hint of the kinds of struggles I would later encounter in high-conflict divorce cases.

During my years at Cornell, I worked at Johnny’s Big Red, a landmark restaurant where Richard Fariña and Thomas Pynchon were regulars. My roles ranged from operating the pizza truck to tending bar and cooking.

One of my most memorable moments was receiving my largest tip from Duke Ellington, a highlight for someone who has always loved big-band jazz.

I also worked as a TV and Hi-Fi repairman. One afternoon, after several futile hours trying to fix a woman’s television, she told me, “You may not be great with TVs, but you’re wonderful with kids.”

She invited me to run the after-school program at her church. That became my first paid job working with children and confirmed the direction my life was heading.

Early Work With Children

After Cornell, I became a counselor at a residential treatment center in Manhattan, serving for four years as a father-surrogate to emotionally disturbed children and teens. That experience taught me more about understanding and helping troubled young people than any formal training that followed, and it firmly established my goal of becoming a child psychologist.

During this period, I immersed myself in the work of Haim Ginott, Virginia Axline, Nathaniel Branden, and Richard Gardner. I first learned of Dr. Gardner’s ideas when The New York Times excerpted his book The Boys and Girls Book About Divorce, the first self-help book written for children navigating their parents’ separation.

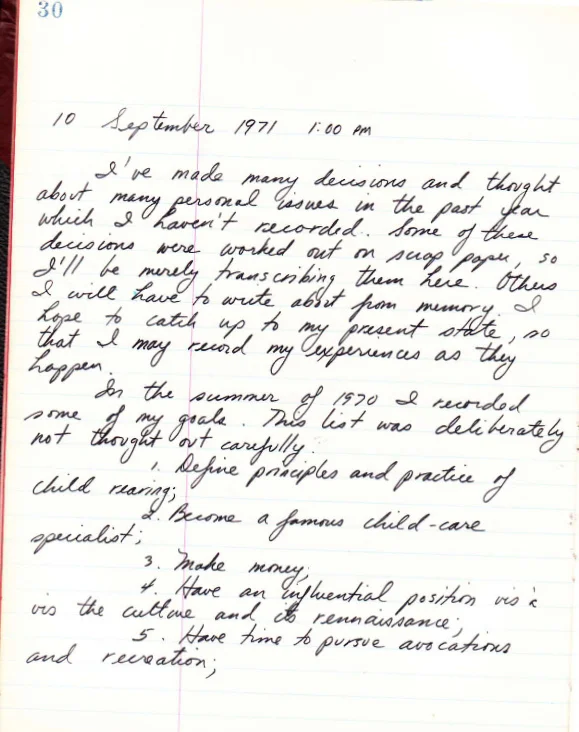

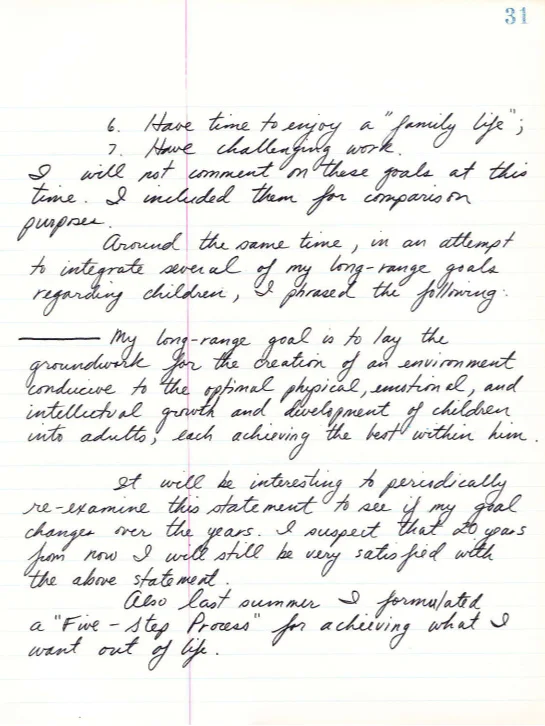

Personal Journal Entry, Referring to Summer 1970, Age 20

Graduate Study and a Shift Toward Research

I entered the Master of Arts program in Psychology at City College of the City University of New York (CCNY), where I was fortunate to study with Ethel Weiss-Shed, Ph.D., and Gertrude Schmeidler, Ph.D. Their commitment to rigorous methodology shaped my own dedication to careful research—an approach that would later define much of my work on divorce and custody.

After passing the examinations to become a candidate for the M.A. degree, and halfway through my thesis research, I was accepted into the doctoral program in clinical psychology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. The program offered immediate admission without requiring me to complete my master’s thesis, and in August 1974 I moved to Texas.

Moving to Texas and the Beginnings of Custody Research

Shortly after arriving in Dallas, I met my future wife, Sandra, at a conference presented by Dr. Gardner on psychotherapy with children and adolescents—the same psychologist whose work had inspired my early interest in the field.

In 1977, during my internship at the Dallas Child Guidance Clinic, the first three children assigned to me were boys from divorced homes who had little contact with their fathers. This pattern prompted questions about the role of divorce and diminished father-child relationships in emotional development. As I dug deeper into the research literature, the data confirmed what I was seeing clinically: children from divorced homes, particularly boys, were more likely to struggle with emotional and behavioral challenges.

Part of my interest in father-absence had personal roots. In 1912, when my father was two years old, his father was killed instantly by a runaway horse and cart. I had always wondered how that loss shaped my father’s childhood and what his life might have looked like if his father had lived.

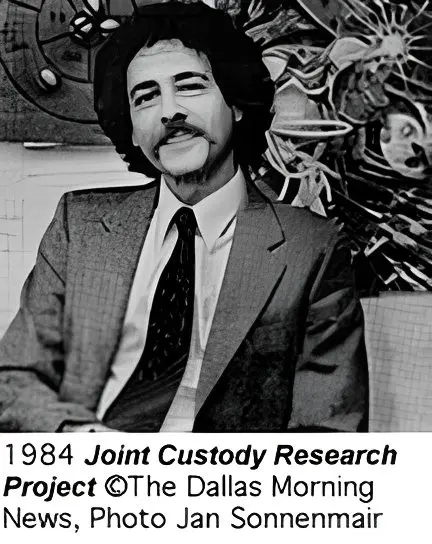

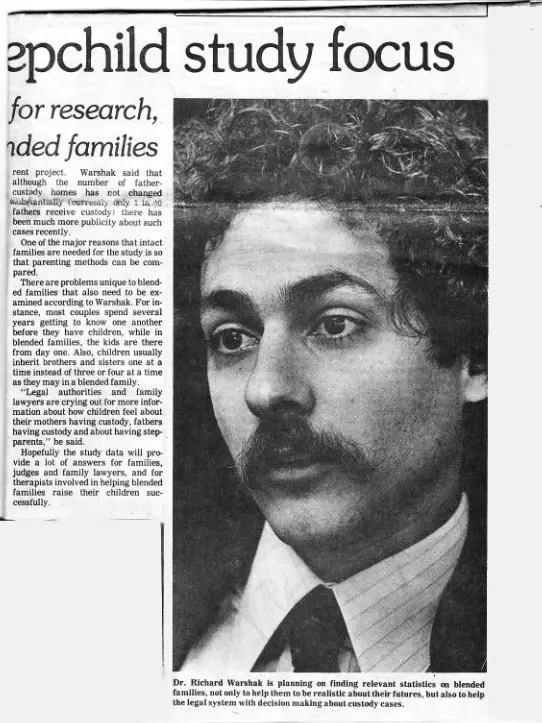

The Texas Custody Research Project

Also in 1977, I joined a graduate seminar led by Professor John Santrock, a leading scholar on father absence and one of the most prolific authors in psychology. At the time, nearly all research on divorce outcomes focused on children living with their mothers. Dr. Santrock invited me to collaborate on the first project that directly compared children living in father-custody homes with those in mother-custody homes.

We designed our studies with rigorous safeguards—carefully matched control groups, reliable measures, and strict methodological standards. These became known as the Texas Custody Research Project. The work earned peer respect and was published in well-regarded academic journals.

In December 1978, I completed my dissertation, The Effects of Father Custody and Mother Custody on Children’s Personality Development.

The media began covering our findings, and Time magazine ran a story about the work. Soon my phone rang constantly with desperate fathers fearful of losing meaningful contact with their children. For the first time, I saw how deeply custody practices could affect families.

The publicity also attracted criticism. Some who disagreed with the implications of the research mistakenly labeled me a fathers’ rights advocate. Over time, my work assisting divorced mothers and highlighting concerns about joint custody in cases involving abuse helped correct that misperception. Reviewers have since praised my balanced treatment of both mothers’ and fathers’ concerns.

Building a Clinical and Professional Life

After earning my Ph.D. in 1978, I joined the Dallas Child Guidance Clinic as a psychologist, consulted weekly with a local school system’s Special Education department, and taught psychology at the University of Texas at Dallas. In 1979, I opened a part-time private practice working with children, adults, and families.

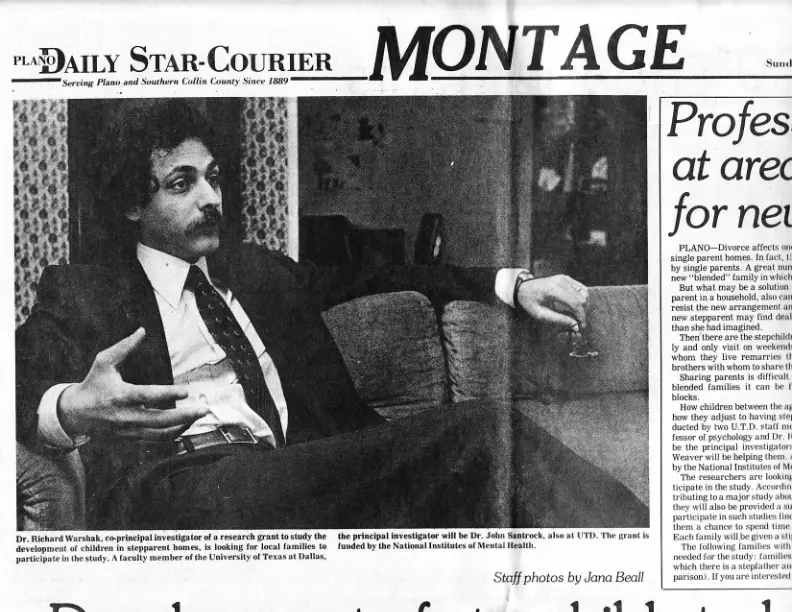

In 1981, Dr. Santrock and I received a large NIMH grant to extend our custody research to stepfamilies, again using rigorous research methods. The results appeared in respected journals, including Child Development, and were frequently cited in academic and legal settings around the world.

Throughout the 1980s, I continued clinical work, research projects, and media consultation. I helped establish the Dallas Society for Psychoanalytic Psychology in 1983, founded its bulletin the following year, and served as Editor-in-Chief for seven years before being elected President.

During this period, I also created the Parent Questionnaire, a tool still used by mental health professionals to better understand the concerns of children and adolescents.

As media interest in divorce and custody increased, I was invited to speak at conferences and, eventually, to contribute as an expert witness in custody trials. I realized that integrating research, clinical experience, and forensic evaluation offered an opportunity to help courts make better decisions for children. That insight shaped much of my future work.

Writing, Public Engagement, and New Directions

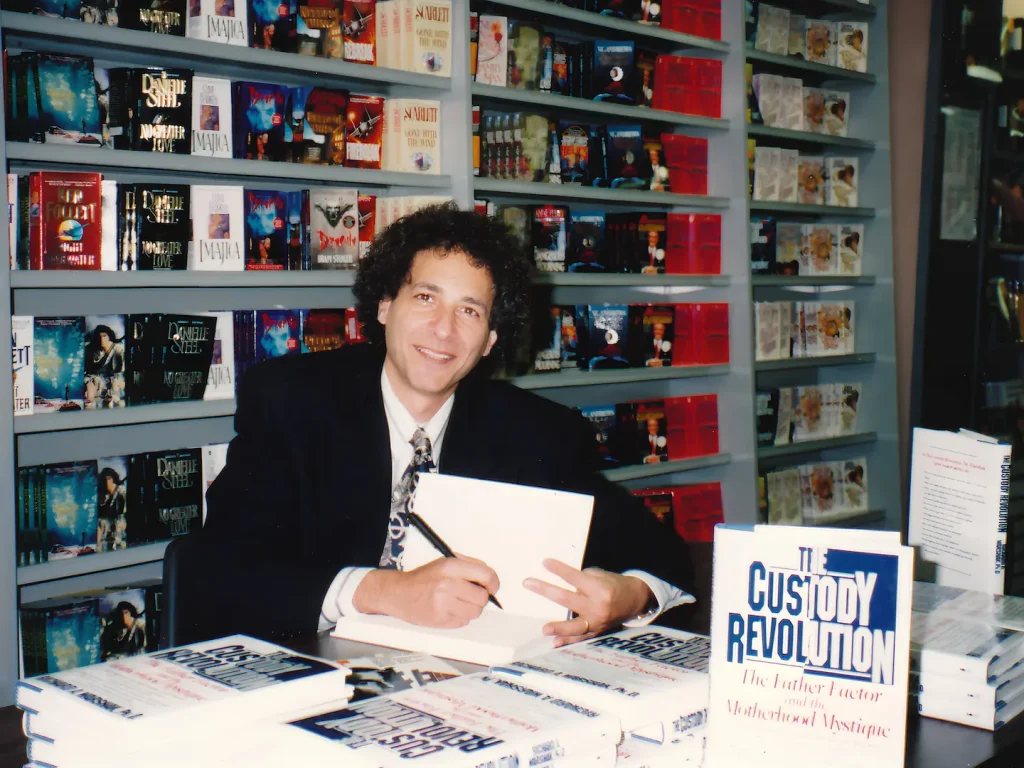

My first book, The Custody Revolution, was published by Simon & Schuster in 1992. It offered practical guidance on custody decisions and proposed reforms that have since become standard practice. A Czech translation followed in 1995.

The year after publication, I was invited to the White House to discuss custody policy and became the youngest person in the Psychology Division at UT Southwestern Medical Center to achieve the rank of Clinical Professor.

During the late 1990s, I focused on some of the most contentious issues in custody litigation: relocation cases, restrictions on young children’s overnights, and parental alienation. My analysis of relocation research led to the widely cited Warshak Brief, endorsed by leading divorce scholars and submitted to the California Supreme Court. The Court’s nearly unanimous ruling aligned with the brief’s conclusion that relocation cases require careful judicial discretion rather than rigid rules.

My article Blanket Restrictions challenged unscientific assumptions that young children should never spend nights with both parents after divorce and contributed to reforms in parenting plans for young children.

My work on parental alienation led to an invitation to write the chapter on the topic for the Expert Witness Manual, and it marked the beginning of a long professional dialogue with Dr. Gardner. Years after I first read his work, we presented keynote lectures together in Frankfurt, shortly before his passing in 2003.

Later Projects and Current Focus

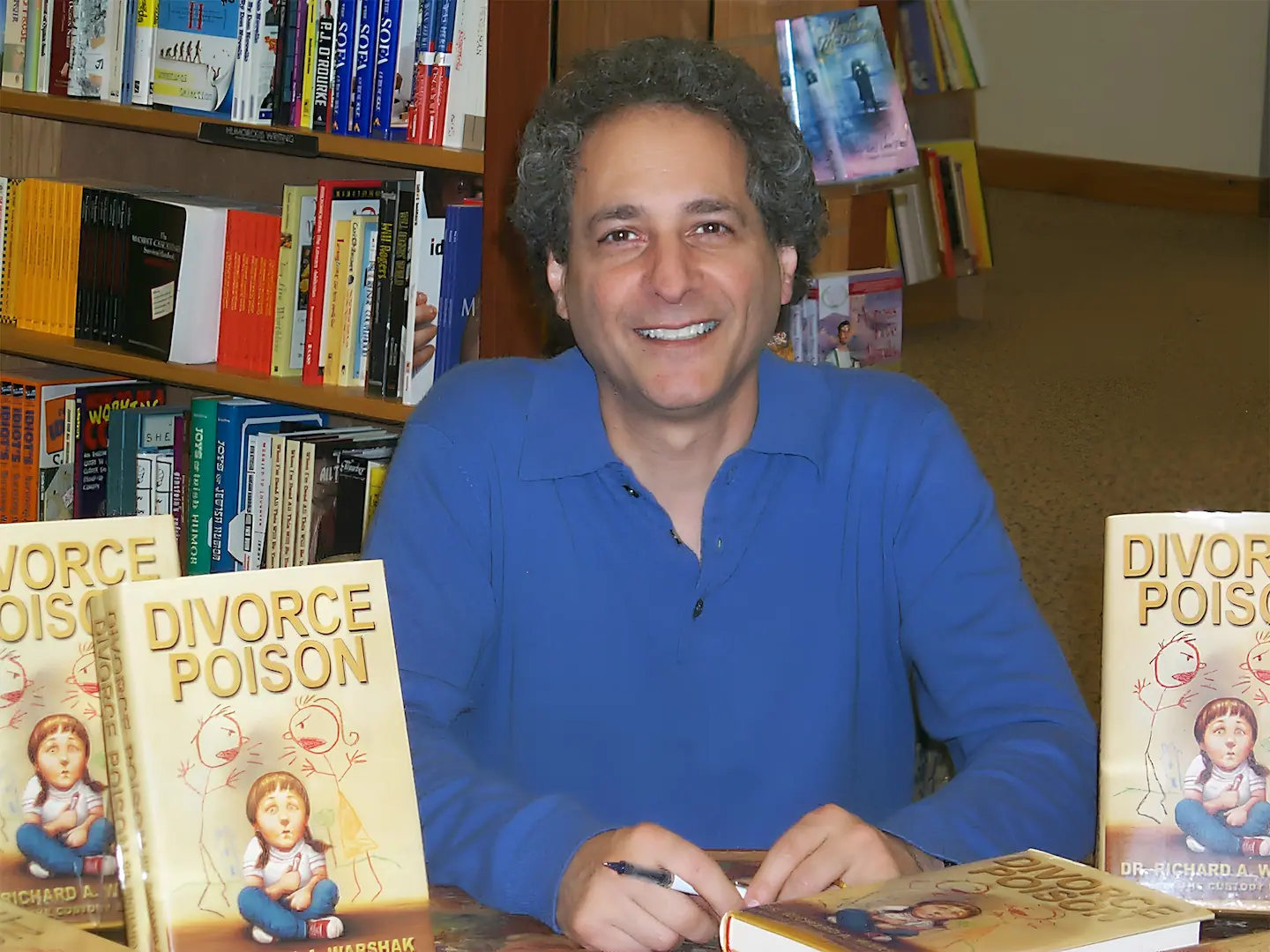

Divorce Poison, first published in 2002 and now in its 25th printing, became the best-selling book on the psychology of alienated children and has been translated into several languages. One of my professional articles was later cited in the German Civil Code regarding cases involving alienated children.

In addition to research and writing, I have continued my office practice, consulted with attorneys, mental health professionals, and families across the globe, and given keynote lectures internationally. These engagements provide opportunities to educate professionals and to refine ideas through dialogue with colleagues.

Recent years have brought a focus on developing interventions to prevent and reverse severe alienation in children and adolescents. This includes training professionals and developing programs such as Family Bridges™, described in the revised edition of Divorce Poison, and the Pluto Center™, which I co-founded in 2009. The Pluto Center’s mission is to promote awareness, understanding, prevention, and healing of disrupted parent-child relationships. Our first project, Welcome Back, Pluto, offers a way to engage reluctant children in understanding alienation and their role in addressing it.

Recognition

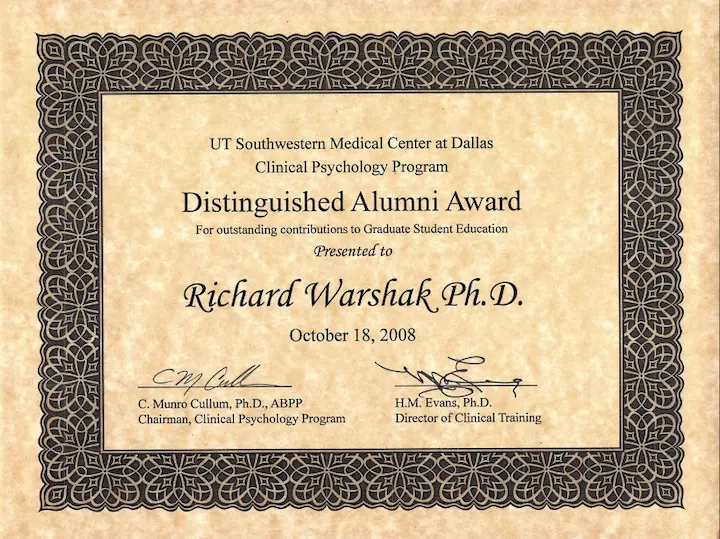

I have been fortunate enough to have my contributions recognized through several awards and accolades throughout the years, such as my Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

More recently, I was honored to have received the Ned Holstein Shared Parenting Research Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Parents Organization. This award recognizes researchers whose work has meaningfully advanced our understanding of parenting arrangements that support children’s well-being when parents live apart.

In presenting the award, the National Parents Organization cited not only my research contributions but also the public outreach that has helped inform legislation and practice—“improving the lives of parents and children around the world.” The award made special note of my 2014 “consensus report” article, endorsed by 110 researchers and practitioners, describing it as “a literally extraordinary article—seldom does one see in social science research a paper of this nature.”

This recognition is especially meaningful to me, as past recipients include some of the world’s foremost scholars in child development. To be counted among them is both humbling and deeply gratifying.

Personal Life

I continue to live and work in Dallas with my wife. I enjoy spending time with my extended family, gourmet cooking, bike riding, and listening to, playing, and writing music.

My musical tastes range from Ella Fitzgerald, Stan Kenton, Don Ellis, and Billie Holiday to Warren Zevon, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Tom Waits.